Time for a libertarian president

+8

che

kiranr

TalkingReckless

Funkentelechy

BarrileteCosmico

Swanhends

RedOranje

Yuri Yukuv

12 posters

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Time for a libertarian president

Time for a libertarian president

NO BAILOUT FOR EUROPE!

Yuri Yukuv- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 1974

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 78

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

No bailout for Europe, because we'd be even worse off economically!

RedOranje- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 11099

Join date : 2011-06-05

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

I will give credit to Ron Paul for this and this alone: He doesn't flip flop, he doesn't pander, and he stands by all of his beliefs (even the unpopular)

With that being said....He's a nutjob!

Abolish the fed are you out of your fking mind?

With that being said....He's a nutjob!

Abolish the fed are you out of your fking mind?

Swanhends- Fan Favorite

- Club Supported :

Posts : 8451

Join date : 2011-06-05

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Yeah even libertarians disagree with that one

BarrileteCosmico- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 28289

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 33

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Ron Paul

Funkentelechy- Starlet

- Club Supported :

Posts : 714

Join date : 2011-10-27

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Even if Ron Paul were president, none of the moves he would suggest would get approved by congress

BarrileteCosmico- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 28289

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 33

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

even though many of his ideas are far fetched and can never happen..... i still think he is the best candidate from the Rep side....in my opinion

he is the one who doesn't constantly change his stance on things to please people...

and i hate gringrich even more now calling Palestine invented people.... Israel is as made up as Palestine....Most of the Jewish people living in Israel aren't descendants of that area, the only thing they have in common is their religion...

Gringrich will probably win, he is going to get huge backing from the Jewish who have alot of $$ for him to spend

he is the one who doesn't constantly change his stance on things to please people...

and i hate gringrich even more now calling Palestine invented people.... Israel is as made up as Palestine....Most of the Jewish people living in Israel aren't descendants of that area, the only thing they have in common is their religion...

Gringrich will probably win, he is going to get huge backing from the Jewish who have alot of $$ for him to spend

TalkingReckless- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 4200

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 32

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

bhends wrote:I will give credit to Ron Paul for this and this alone: He doesn't flip flop, he doesn't pander, and he stands by all of his beliefs (even the unpopular)

With that being said....He's a nutjob!

Abolish the fed are you out of your fking mind?

What did he propose as substitute or what was his idea in general?

kiranr- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 3496

Join date : 2011-06-06

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

at this point america could have a hybrid of jesus, gandhi, buffett and hawking as president and it wouldn't help because congress parties will always disagree with each other for the sake of disagreeing

che- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 3597

Join date : 2011-06-05

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

che wrote:at this point america could have a hybrid of jesus, gandhi, buffett and hawking as president and it wouldn't help because congress parties will always disagree with each other for the sake of disagreeing

true

Swanhends- Fan Favorite

- Club Supported :

Posts : 8451

Join date : 2011-06-05

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Kirarnr, he wants to go back to the gold standard. Which means that during recessions the US would not be able to keep aggregate demand at a stable place through monetary policy and it would make recessions worse. It was abandoning the gold standard that made getting out of the Great Recession possible.

BarrileteCosmico- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 28289

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 33

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Actually Ron Paul doesn't advocate abolishing the fed any time during his presidency or returning to the gold standard, but rather to stop the monopoly on money coinage and minting by the federal, here is his solution:

Over millennia of human history, gold and silver have been the two metals that have most often satisfied the market's demand for money and gained the trust of billions of people. Gold and silver are difficult to counterfeit, a property which ensures they will always be accepted in commerce. It is precisely for this reason that gold and silver are anathema to governments. A supply of gold and silver that is limited in supply by nature cannot be inflated, and thus serves as a check on the growth of government. Without the ability to inflate the currency, governments find themselves constrained in their actions, unable to fund either the welfare state or the warfare state.

On the desk in my office I have a sign that says: "Don't steal – the government hates competition." Indeed, any power a government arrogates to itself, it is loathe to give back to the people. The history of this nation is filled with examples of increasing and unconstitutional centralization of power by the federal government. Militias, letters of marque and reprisal, and declarations of war have gone by the wayside; the postal monopoly drove out private competition; and a market-driven system of competing currencies was suppressed by the creation of a government-supported banking cartel that monopolizes the issuance of currency. In order to return to sound money, it is necessary to undo the legal obstacles that forbid other currencies from competing against the dollar.

The first step consists of eliminating legal tender laws. Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution forbids the States from making anything but gold and silver a legal tender in payment of debts. States are not required to enact legal tender laws, but should they choose to, the only acceptable legal tender is gold and silver, the two precious metals that individuals throughout history and across cultures have used as currency. There is nothing in the Constitution that grants Congress the power to enact legal tender laws. Congress has the power to coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, but not to declare a legal tender. Yet, there is a section of US Code, 31 USC 5103, that purports to establish US coins and currency, including Federal Reserve notes, as legal tender.

Historically, legal tender laws have been used by governments to force their citizens to accept debased and devalued currency. Gresham's Law describes this phenomenon, which can be summed up in one phrase: bad money drives out good money. An emperor, a king, or a dictator might mint coins with half an ounce of gold and force merchants, under pain of death, to accept them as though they contained one ounce of gold. Each ounce of the king's gold could now be minted into two coins instead of one, so the king now had twice as much "money" to spend on building castles and raising armies. As these legally overvalued coins circulated, the coins containing the full ounce of gold would be pulled out of circulation and hoarded. This same phenomenon occurred in the United States in the mid-1960s when the US government began to mint subsidiary coinage out of copper and nickel rather than silver. The copper and nickel coins were legally overvalued, the silver coins undervalued in relation, and silver coins vanished from circulation.

These actions also give rise to the most pernicious effects of inflation. Once the public realized that the king debased his currency by 50%, prices would eventually double, as it would now take two coins to purchase what used to require only one. The king who debased his currency spent his new money immediately, before prices rose, and thus gained the benefit of that new money. Most of the merchants and peasants who received the devalued currency felt the full effects of inflation, the rise in prices and the lowered standard of living, before they received any of the new currency. By the time they received the new currency, they had long since had to suffer doubled prices, and the new currency they received would give them no benefit. In the absence of legal tender laws, Gresham's Law no longer holds. If people are free to reject debased currency, and instead demand sound money, sound money will gradually return to use in society.

The second step to legalizing currency competition is to eliminate laws that prohibit the operation of private mints. One private enterprise which attempted to popularize the use of precious metal coins was Liberty Services, the creators of the Liberty Dollar. The government felt threatened by the Liberty Dollar, as Liberty Services had all their precious metal coins seized by the FBI and Secret Service in November of 2007.

The sections of US Code which Liberty Services is accused of violating are categorized as anti-counterfeiting statutes, when in fact their purpose was to shut down private mints that had been operating in California. California was awash in gold in the aftermath of the 1849 gold rush, yet had no US Mint to mint coinage. Even establishment of a US Assay Office failed to provide enough coinage, as the only coins they produced were too large to be used in everyday transactions. Foreign coins filled the void, but even still there was insufficient coinage, and these coins circulated at a value higher than their inherent metal value. The public clamored for smaller denominations of coins, and private mints stepped into the breech to fulfill this demand. The private mints were eventually accused of circulating debased coinage, and with the supposed aim of providing government-sanctioned regulation and a government guarantee of purity, federal laws were enacted which banned private mints from producing their own coins for circulation as currency.

The final step to reestablishing competition in currency is to eliminate capital gains and sales taxes on gold and silver coins. Under current federal law, coins are considered collectibles, and are liable for capital gains taxes. Coins held for less than one year are taxed at the short-term capital gains rate, which is the normal income tax rate, while coins held for more than a year are taxed at the collectibles rate of 28 percent. These taxes on coins actually tax monetary debasement. The purchasing power of gold remains relatively constant, but as the nominal dollar value of gold increases due to the weakening of the dollar by the Federal Reserve, the federal government considers this to be an increase in wealth, and taxes accordingly. Thus, the more the dollar is debased, the more capital gains taxes must be paid on holdings of gold and other precious metals.

Just as pernicious are the sales and use taxes which are assessed on gold and silver at the state level in many states. Imagine having to pay sales tax at the bank every time you change a $10 bill for a roll of quarters to do laundry. Inflation is a pernicious tax on the value of money, but even the official numbers, which are massaged downwards, are only on the order of 3-4% per year. Sales taxes in many states can take away 8% or more on every single transaction in which consumers wish to convert their Federal Reserve Notes into gold or silver coins. Americans should not be penalized through punitive taxation merely for desiring to hold or use one type of currency, nor should they be penalized for exchanging Federal Reserve Notes for US Mint-produced coins.

I hope that this hearing will start a vigorous discussion of currency competition, sound money, and how to return to a sound dollar. HR 1098 is certainly not a panacea, as there remain significant structural problems in our banking and monetary system that still need to be addressed. But allowing for competing currencies will enable Americans to choose a currency that suits their needs, rather than the needs of the government. The prospect of Americans turning away from the dollar towards alternate currencies will provide the necessary impetus to the US government to regain control of the dollar and halt its downward spiral. Restoring soundness to the dollar will remove the government's ability and incentive to inflate the currency, and keep us from launching unconstitutional wars that burden our economy to excess. With a sound currency, everyone is better off, not just those who control the monetary system.

Over millennia of human history, gold and silver have been the two metals that have most often satisfied the market's demand for money and gained the trust of billions of people. Gold and silver are difficult to counterfeit, a property which ensures they will always be accepted in commerce. It is precisely for this reason that gold and silver are anathema to governments. A supply of gold and silver that is limited in supply by nature cannot be inflated, and thus serves as a check on the growth of government. Without the ability to inflate the currency, governments find themselves constrained in their actions, unable to fund either the welfare state or the warfare state.

On the desk in my office I have a sign that says: "Don't steal – the government hates competition." Indeed, any power a government arrogates to itself, it is loathe to give back to the people. The history of this nation is filled with examples of increasing and unconstitutional centralization of power by the federal government. Militias, letters of marque and reprisal, and declarations of war have gone by the wayside; the postal monopoly drove out private competition; and a market-driven system of competing currencies was suppressed by the creation of a government-supported banking cartel that monopolizes the issuance of currency. In order to return to sound money, it is necessary to undo the legal obstacles that forbid other currencies from competing against the dollar.

The first step consists of eliminating legal tender laws. Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution forbids the States from making anything but gold and silver a legal tender in payment of debts. States are not required to enact legal tender laws, but should they choose to, the only acceptable legal tender is gold and silver, the two precious metals that individuals throughout history and across cultures have used as currency. There is nothing in the Constitution that grants Congress the power to enact legal tender laws. Congress has the power to coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, but not to declare a legal tender. Yet, there is a section of US Code, 31 USC 5103, that purports to establish US coins and currency, including Federal Reserve notes, as legal tender.

Historically, legal tender laws have been used by governments to force their citizens to accept debased and devalued currency. Gresham's Law describes this phenomenon, which can be summed up in one phrase: bad money drives out good money. An emperor, a king, or a dictator might mint coins with half an ounce of gold and force merchants, under pain of death, to accept them as though they contained one ounce of gold. Each ounce of the king's gold could now be minted into two coins instead of one, so the king now had twice as much "money" to spend on building castles and raising armies. As these legally overvalued coins circulated, the coins containing the full ounce of gold would be pulled out of circulation and hoarded. This same phenomenon occurred in the United States in the mid-1960s when the US government began to mint subsidiary coinage out of copper and nickel rather than silver. The copper and nickel coins were legally overvalued, the silver coins undervalued in relation, and silver coins vanished from circulation.

These actions also give rise to the most pernicious effects of inflation. Once the public realized that the king debased his currency by 50%, prices would eventually double, as it would now take two coins to purchase what used to require only one. The king who debased his currency spent his new money immediately, before prices rose, and thus gained the benefit of that new money. Most of the merchants and peasants who received the devalued currency felt the full effects of inflation, the rise in prices and the lowered standard of living, before they received any of the new currency. By the time they received the new currency, they had long since had to suffer doubled prices, and the new currency they received would give them no benefit. In the absence of legal tender laws, Gresham's Law no longer holds. If people are free to reject debased currency, and instead demand sound money, sound money will gradually return to use in society.

The second step to legalizing currency competition is to eliminate laws that prohibit the operation of private mints. One private enterprise which attempted to popularize the use of precious metal coins was Liberty Services, the creators of the Liberty Dollar. The government felt threatened by the Liberty Dollar, as Liberty Services had all their precious metal coins seized by the FBI and Secret Service in November of 2007.

The sections of US Code which Liberty Services is accused of violating are categorized as anti-counterfeiting statutes, when in fact their purpose was to shut down private mints that had been operating in California. California was awash in gold in the aftermath of the 1849 gold rush, yet had no US Mint to mint coinage. Even establishment of a US Assay Office failed to provide enough coinage, as the only coins they produced were too large to be used in everyday transactions. Foreign coins filled the void, but even still there was insufficient coinage, and these coins circulated at a value higher than their inherent metal value. The public clamored for smaller denominations of coins, and private mints stepped into the breech to fulfill this demand. The private mints were eventually accused of circulating debased coinage, and with the supposed aim of providing government-sanctioned regulation and a government guarantee of purity, federal laws were enacted which banned private mints from producing their own coins for circulation as currency.

The final step to reestablishing competition in currency is to eliminate capital gains and sales taxes on gold and silver coins. Under current federal law, coins are considered collectibles, and are liable for capital gains taxes. Coins held for less than one year are taxed at the short-term capital gains rate, which is the normal income tax rate, while coins held for more than a year are taxed at the collectibles rate of 28 percent. These taxes on coins actually tax monetary debasement. The purchasing power of gold remains relatively constant, but as the nominal dollar value of gold increases due to the weakening of the dollar by the Federal Reserve, the federal government considers this to be an increase in wealth, and taxes accordingly. Thus, the more the dollar is debased, the more capital gains taxes must be paid on holdings of gold and other precious metals.

Just as pernicious are the sales and use taxes which are assessed on gold and silver at the state level in many states. Imagine having to pay sales tax at the bank every time you change a $10 bill for a roll of quarters to do laundry. Inflation is a pernicious tax on the value of money, but even the official numbers, which are massaged downwards, are only on the order of 3-4% per year. Sales taxes in many states can take away 8% or more on every single transaction in which consumers wish to convert their Federal Reserve Notes into gold or silver coins. Americans should not be penalized through punitive taxation merely for desiring to hold or use one type of currency, nor should they be penalized for exchanging Federal Reserve Notes for US Mint-produced coins.

I hope that this hearing will start a vigorous discussion of currency competition, sound money, and how to return to a sound dollar. HR 1098 is certainly not a panacea, as there remain significant structural problems in our banking and monetary system that still need to be addressed. But allowing for competing currencies will enable Americans to choose a currency that suits their needs, rather than the needs of the government. The prospect of Americans turning away from the dollar towards alternate currencies will provide the necessary impetus to the US government to regain control of the dollar and halt its downward spiral. Restoring soundness to the dollar will remove the government's ability and incentive to inflate the currency, and keep us from launching unconstitutional wars that burden our economy to excess. With a sound currency, everyone is better off, not just those who control the monetary system.

Yuri Yukuv- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 1974

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 78

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Not all libertarians share the belief that we should return to the gold standard, I myself am not one of them. There are numerous other suggestion which I would reckon congressman Ron Paul would find reasonable.

The main problem we have is that interest rates and by extension inflation are centrally controlled by unelected persons, I think that there is no need for human discretion as we can use computer programs in order to calculate the desired rate without any need for human input.

I for one am a big believer in the monetarist school, the major central banks of the world (FED and ECB) are actually based on this school but they all seem to like withhold power on this particular issue and diverge from the optimum mechanism

Back on '05 we said that this a bubble

The main problem we have is that interest rates and by extension inflation are centrally controlled by unelected persons, I think that there is no need for human discretion as we can use computer programs in order to calculate the desired rate without any need for human input.

I for one am a big believer in the monetarist school, the major central banks of the world (FED and ECB) are actually based on this school but they all seem to like withhold power on this particular issue and diverge from the optimum mechanism

Back on '05 we said that this a bubble

Yuri Yukuv- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 1974

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 78

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Have any of you read about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)? It is in its infancy and just being developed. It is an offshoot of Keynesian Monetary theory and it makes a lot of sense. Much of the current problems could be avoided if the governments all over the world followed it.

kiranr- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 3496

Join date : 2011-06-06

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Yuri how would you calculate the desired rate of inflation through computers? What kind of system would you use? How would this system deal with the zero bound rate?

I think the current dual mandate system is fine, and you do need people in there to make this kind of call. They might make mistakes, but they're only human. I also think they have the best interests at heart.

Kiranr what does MMT suggest?

I think the current dual mandate system is fine, and you do need people in there to make this kind of call. They might make mistakes, but they're only human. I also think they have the best interests at heart.

Kiranr what does MMT suggest?

BarrileteCosmico- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 28289

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 33

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

The current system in America is quite perfect. The policies are not though.

About MMT, here is the link that explains it in very simple terms. It is a pdf file. Please read it and come back here with your opinions.

http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

About MMT, here is the link that explains it in very simple terms. It is a pdf file. Please read it and come back here with your opinions.

http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

kiranr- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 3496

Join date : 2011-06-06

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

BarrileteCosmico wrote:Yuri how would you calculate the desired rate of inflation through computers? What kind of system would you use? How would this system deal with the zero bound rate?

I think the current dual mandate system is fine, and you do need people in there to make this kind of call. They might make mistakes, but they're only human. I also think they have the best interests at heart.

Kiranr what does MMT suggest?

First off, I just want to say I cant believe that an argentine wants to give me monetary advice...

Just kidding

Its very simple you basically calculate the interest rate imposed by the CB through taking a multitude of factors including inflation, housing price, stock prices, GDP growth and intended GDP. The main aim is to steadily increase money supply with GDP (with the exception of severe cases of liquidity crunches where you would be offset by housing and stock prices). The data is simply entered real time into a computer at every FOMC meeting and then an interest rate is determined, one example of this is the taylor rule which has the following equation.

as wiki explains it:

In this equation, is the target short-term nominal interest rate (e.g. the federal funds rate in the US), is the rate of inflation as measured by the GDP deflator, is the desired rate of inflation, is the assumed equilibrium real interest rate, is the logarithm of real GDP, and is the logarithm of potential output, as determined by a linear trend.

In this equation, both aπ and ay should be positive (as a rough rule of thumb, Taylor's 1993 paper proposed setting aπ = ay = 0.5).[4] That is, the rule "recommends" a relatively high interest rate (a "tight" monetary policy) when inflation is above its target or when output is above its full-employment level, in order to reduce inflationary pressure. It recommends a relatively low interest rate ("easy" monetary policy) in the opposite situation, to stimulate output. Sometimes monetary policy goals may conflict, as in the case of stagflation, when inflation is above its target while output is below full employment. In such a situation, a Taylor rule specifies the relative weights given to reducing inflation versus increasing output.

The federal reserve actually used a variant of this formula to compute almost all interest rates since the days of volcker, they diverged from this in 2004-2005 and after that we had the bubble which eventually caused the crash.

ZIRP is possible using this formula, it is not an issue at all.

The problem is not the federal reserve governers per say but rather how congress and the administration can basically force them into funding the warfare state or the welfare state just as the social conservatives did in the mid 2000's or the liberals did pre-Reagan.

It was never the intention of libertarians to stop the fed because of it in itself but rather how the mechanism it operates in can be used to redistribute wealth of society, mislocate capital to non productive industries and skew economy to aid the state.

Yuri Yukuv- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 1974

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 78

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Here is a little something something from Iowa polls:

As Disenchantment With Idiocy Surges, Ron Paul Support Soars

Every legacy media and central planner's worst nightmare is slowly coming true: as the broader field of GOP candidates is rapidly dropping like US secret drones blowing up nuclear power plants in Iran, due to general idiocy, incompetence, too much baggage-ness or general reverse American Idol syndrome where Americans get tired with any given "leader" only to vote them out of the primary the following week, the one clear winner is becoming Ron Paul, who according to Public Policy Polling has seen his support soar in the past week and is now neck and neck with presidential candidate du week, Newt Gingrich. From the PPP: "There has been some major movement in the Republican Presidential race in Iowa over the last week, with what was a 9 point lead for Newt Gingrich now all the way down to a single point. Gingrich is at 22% to 21% for Paul with Mitt Romney at 16%, Michele Bachmann at 11%, Rick Perry at 9%, Rick Santorum at 8%, Jon Huntsman at 5%, and Gary Johnson at 1%."

More on this news which will be welcomed by supporters of the only person in the GOP crowd who actually deserves to be president:

Paul meanwhile has seen a big increase in his popularity from +14 (52/38) to +30 (61/31). There are a lot of parallels between Paul's strength in Iowa and Barack Obama's in 2008- he's doing well with new voters, young voters, and non-Republican voters:

-59% of likely voters participated in the 2008 Republican caucus and they support Gingrich 26-18. But among the 41% of likely voters who are 'new' for 2012 Paul leads Gingrich 25-17 with Romney at 16%. Paul is doing a good job of bringing out folks who haven't done this before.

-He's also very strong with young voters. Among likely caucus goers under 45 Paul is up 30-16 on Gingrich. With those over 45, Gingrich leads him 26-15 with Romney at 17%.

-Among Republicans Gingrich leads Paul 25-17. But with voters who identify as Democrats or independents, 21% of the electorate in a year with no action on the Democratic side, Paul leads Gingrich 34-14 with Romney at 17%.

Young voters, independents, and folks who haven't voted in caucuses before is an unusual coalition for a Republican candidate...the big question is whether these folks will really come out and vote...if they do, we could be in for a big upset.

And if Paul can sustain the surge in momentum from Iowa, he may we have a chance to take New Hampshire where Romney still has a modest lead according to Rasmussen:

Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney remains on top of the New Hampshire Republican Primary field, but the race for second place between Newt Gingrich and Ron Paul is a lot closer than it was just two weeks ago.

The latest Rasmussen Reports statewide telephone survey of Likely Republican Primary Voters shows Romney with 33% of the vote, followed by Gingrich at 22%. Paul now picks up 18% support, his best showing in the Granite State so far. Former Utah Governor Jon Huntsman comes in fourth with 10% of the vote, with no other candidate reaching double digits. (To see survey question wording, click here.)

Support for Romney, Gingrich and Huntsman is little changed from the previous survey, but Paul has now closed the 10-point gap between him and Gingrich to just four points.

Luckily, there still is more than enough opportunity for the other candidates' broad stupidity to shine through, which will benefit only one of the candidates. Furthermore, should the global economy collapse and the Fed proceed with doing the only thing he knows how to do, and as a result focus the broader population's attention even more on monetary policy, there will be only one winner: the one who has made the Fed his nemesis not only during this presidential election cycle, but his entire career.

We wish him all the best.

As Disenchantment With Idiocy Surges, Ron Paul Support Soars

Every legacy media and central planner's worst nightmare is slowly coming true: as the broader field of GOP candidates is rapidly dropping like US secret drones blowing up nuclear power plants in Iran, due to general idiocy, incompetence, too much baggage-ness or general reverse American Idol syndrome where Americans get tired with any given "leader" only to vote them out of the primary the following week, the one clear winner is becoming Ron Paul, who according to Public Policy Polling has seen his support soar in the past week and is now neck and neck with presidential candidate du week, Newt Gingrich. From the PPP: "There has been some major movement in the Republican Presidential race in Iowa over the last week, with what was a 9 point lead for Newt Gingrich now all the way down to a single point. Gingrich is at 22% to 21% for Paul with Mitt Romney at 16%, Michele Bachmann at 11%, Rick Perry at 9%, Rick Santorum at 8%, Jon Huntsman at 5%, and Gary Johnson at 1%."

More on this news which will be welcomed by supporters of the only person in the GOP crowd who actually deserves to be president:

Paul meanwhile has seen a big increase in his popularity from +14 (52/38) to +30 (61/31). There are a lot of parallels between Paul's strength in Iowa and Barack Obama's in 2008- he's doing well with new voters, young voters, and non-Republican voters:

-59% of likely voters participated in the 2008 Republican caucus and they support Gingrich 26-18. But among the 41% of likely voters who are 'new' for 2012 Paul leads Gingrich 25-17 with Romney at 16%. Paul is doing a good job of bringing out folks who haven't done this before.

-He's also very strong with young voters. Among likely caucus goers under 45 Paul is up 30-16 on Gingrich. With those over 45, Gingrich leads him 26-15 with Romney at 17%.

-Among Republicans Gingrich leads Paul 25-17. But with voters who identify as Democrats or independents, 21% of the electorate in a year with no action on the Democratic side, Paul leads Gingrich 34-14 with Romney at 17%.

Young voters, independents, and folks who haven't voted in caucuses before is an unusual coalition for a Republican candidate...the big question is whether these folks will really come out and vote...if they do, we could be in for a big upset.

And if Paul can sustain the surge in momentum from Iowa, he may we have a chance to take New Hampshire where Romney still has a modest lead according to Rasmussen:

Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney remains on top of the New Hampshire Republican Primary field, but the race for second place between Newt Gingrich and Ron Paul is a lot closer than it was just two weeks ago.

The latest Rasmussen Reports statewide telephone survey of Likely Republican Primary Voters shows Romney with 33% of the vote, followed by Gingrich at 22%. Paul now picks up 18% support, his best showing in the Granite State so far. Former Utah Governor Jon Huntsman comes in fourth with 10% of the vote, with no other candidate reaching double digits. (To see survey question wording, click here.)

Support for Romney, Gingrich and Huntsman is little changed from the previous survey, but Paul has now closed the 10-point gap between him and Gingrich to just four points.

Luckily, there still is more than enough opportunity for the other candidates' broad stupidity to shine through, which will benefit only one of the candidates. Furthermore, should the global economy collapse and the Fed proceed with doing the only thing he knows how to do, and as a result focus the broader population's attention even more on monetary policy, there will be only one winner: the one who has made the Fed his nemesis not only during this presidential election cycle, but his entire career.

We wish him all the best.

Yuri Yukuv- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 1974

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 78

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Yuri, I suspected you might bring up the Taylor rule, but it's worth noticing that the Taylor rule itself has a series of shortcomings. For one, there are many "Taylor rules" available, the most common one is the one where the 2 exponents are .5 but that is not the case for the federal reserve, that actually uses an adapted version to their needs. So there's many rules available, and it's not exactly clear which one to use (and they actually do keep pretty close to it, so if your complaint is that they don't follow it then I honestly have to say I don't see where you're coming from, but I now see your complaint as more on the independence side than policy). Perhaps more importantly, the Taylor rule is negative right now, and negative rates can't happen because the only way people would accept negative nominal rates is if they were forced into it, otherwise they'd rather have cash. Then there's the fact that monetary policy is not just deciding the target FFR, this is just one of the many tools available to policymakers. Finally, Taylor himself has stated that his "rule" is just a guideline and should not be used in a strict manner for policymaking. Also, I doubt that they've been using this since the Volcker years since I think the paper came out in 1994

But I do agree that the central bank could be more independent and that this would be surely beneficial. Less influence from congress is surely a good thing, Dodd-Frank is a step in the opposite direction.

And I can see the irony with me being Argentine. But in fairness, we encourage inflation, we think it pushes consumption upwards, which might overheat our economy, but what's 25% compared to the 3000% we had 20 years ago?

Although if I were president the first thing I would do would be to establish a credible, independent central bank with some form of inflation-targeting (PLT, perhaps), and maybe eventually move into NGDP targeting.

Kiranr I still haven't had a chance to read through those 63 pages, finals week and all that.

But I do agree that the central bank could be more independent and that this would be surely beneficial. Less influence from congress is surely a good thing, Dodd-Frank is a step in the opposite direction.

And I can see the irony with me being Argentine. But in fairness, we encourage inflation, we think it pushes consumption upwards, which might overheat our economy, but what's 25% compared to the 3000% we had 20 years ago?

Although if I were president the first thing I would do would be to establish a credible, independent central bank with some form of inflation-targeting (PLT, perhaps), and maybe eventually move into NGDP targeting.

Kiranr I still haven't had a chance to read through those 63 pages, finals week and all that.

BarrileteCosmico- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 28289

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 33

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

You have a great reply, however I disagree with you on something and I think you are slightly misinformed in others. I will come back to answer by the weekend.

For now however I will adress part of your reply with an article written by Taylor himself

This is a great read for anyone

[u]

[u]

For now however I will adress part of your reply with an article written by Taylor himself

This is a great read for anyone

The cycle of rules and discretion in the economy

On December 28, 1948, the famed financier Winthrop Aldrich — who was then serving as president of the nation's largest bank, Chase National — addressed the first joint luncheon of the American Economic Association and the American Finance Association. The two groups — and, with them, the larger community of American economists — were struggling to find a way out of the seemingly endless economic state of emergency America had experienced in the prior two decades, and to shape a post-war approach to macroeconomic policy. In his remarks, Aldrich took up a theme that would reverberate throughout the post-war era: the question of whether monetary policy should be guided by the goal of long-term price stability or yield to short-term pressures to keep interest rates low.

Aldrich blamed the Federal Reserve's easy-money policies of the 1920s for helping to cause the Great Depression. In the late '40s, he was concerned that the Fed would monetize the enormous World War II debt, printing money to buy up Treasury bonds and thereby increasing the risk of inflation. "The goal of the monetary authorities," he said, should instead be to "modify the policy of maintaining rigid support levels for government bonds and to regain their freedom" to combat long-term inflation.

The following year, the groups' second joint luncheon address was given by Paul Douglas, the University of Chicago economist who had just been elected to the U.S. Senate from Illinois. Douglas's themes were similar to Aldrich's, though he focused on fiscal policy. He knew the Keynesian arguments for short-term deficit spending but was concerned about the national debt: "[T]he problem of balancing the budget and of adopting a sound fiscal policy is not merely economic," Douglas argued. "It is to an even greater degree a moral issue. We shall need a proper sense of values and a high degree of ethical self-restraint if we are to reach our goal."

The question that concerned Aldrich and Douglas more than 60 years ago — the question of the basic ends and means of American fiscal and monetary policy — has been hotly disputed ever since. That dispute has often centered on the merits of rules-based policymaking versus those of discretionary policymaking. Of course, fiscal and monetary policies always involve some combination of rules and discretion: Policymakers never simply employ one approach or another by itself. But they do, at different times and in response to different pressures, tend to emphasize one over the other.

When policymakers lean in the direction of rules, they pursue less interventionist, more predictable, and more systematic policies. In monetary policy, the Federal Reserve adheres to a steady and predictable strategy for adjusting interest rates or the money supply. In fiscal policy, legislators and executive-branch officials set long-term debt, spending, and revenue policies and rely on "automatic stabilizers" — such as unemployment benefits and other transfer programs that are sensitive to changes in the business cycle — to counteract booms or busts.

When policymakers lean toward discretion, by contrast, they pursue less predictable, more interventionist policies with a focus on short-term fine-tuning. In monetary policy, the Federal Reserve seeks to influence or respond to momentary fluctuations in unemployment and inflation without a long-term strategy. Fiscal policy comes to involve targeted and temporary spending and tax changes, the goals of which are usually to produce a short-term stimulus.

Economic policy during the post-war period has consisted of three major oscillations between rules-based and discretionary policy. The first swing moved toward more discretionary policies in the 1960s and '70s; then came a shift toward more rules-based policies in the 1980s and '90s. In the past decade, there has been a return to discretion. Remarkably, the same oscillations occurred simultaneously in both monetary and fiscal policy. Each of these swings has had enormous consequences for the American economy. Taken together, they make for a historical proving ground in which to study the effects of rules-based and discretionary policies on the economy.

So what, then, might we learn from this evidence about the effects of these policies on unemployment, inflation, economic stability, the frequency and depths of recessions, the length and strength of recoveries, and periods of economic growth? What does history suggest about the question that concerned Aldrich and Douglas, and that has consumed countless economic thinkers since? When it comes to fostering prosperity, which is better — sticking to clear rules, or granting policymakers broad discretion?

THREE SWINGS

In the decades following World War II, Keynesian ideas about countercyclical fiscal policy became increasingly popular among academic economists. This developing consensus received an official imprimatur when the 1962 Economic Report of the President — the annual publication produced by the President's Council of Economic Advisers — made an explicit case for significant discretion in economic policy. "The task of economic stabilization cannot be left entirely to built-in stabilizers," the report warned. "Discretionary budget policy, e.g., changes in tax rates or expenditure programs, is indispensible — sometimes to reinforce, sometimes to offset, the effects of the stabilizers." The council further argued that the government should have broad leeway to make such changes frequently, in response to evolving conditions: "In order to promote economic stability, the Government should be able to change quickly tax rates or expenditure programs, and equally able to reverse its actions as circumstances change," the report noted. According to the council, a similar logic must prevail in monetary policy — where "[d]iscretionary policy is essential, sometimes to reinforce, sometimes to mitigate or overcome, the monetary consequences of short-run fluctuations of economic activity."

These general principles soon started to be expressed in policy — and they continued to be throughout the 1960s and '70s, under administrations from both parties. By and large, they took the form of stimulus packages and other targeted spending or temporary tax changes intended to drive demand or otherwise manipulate the economy. They included the investment tax credit of 1962, and tax surcharge of 1968, and the tax rebate of 1975. As late as 1977, the Carter administration successfully enacted discretionary stimulus packages, including sizable grants to the states for infrastructure.

The epitome of interventionist economic policy, though, was the imposition of wage and price controls by the Nixon administration in 1971 to combat inflation, which had climbed above 6% the previous year. The original 90-day freeze on nearly all wage and price increases expanded into a three-year experiment in discretionary inflation control — an experiment that ultimately failed. (In 1974, the average inflation rate was above 11%.)

These interventionist measures had the support of that era's most prominent voices in monetary policy. Indeed, in 1972, Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns defended the administration's efforts; the reason, he explained to another joint luncheon of the American Economic Association and the American Finance Association, was that "wage rates and prices no longer respond as they once did to the play of market forces." Burns applied the same interventionist approach to his role at the Fed, and the late 1960s and '70s saw a series of discretionary adjustments of the money supply and interest rates. No one, it seems, was heeding Milton Friedman's counsel — offered in his own American Economic Association address in 1967 — that the Federal Reserve should go about "setting itself a steady course and keeping to it."

A great deal of subsequent research has shown that the Fed's responses to inflation were highly unstable over this period of discretion. Those responses can be divided into several distinct boom-bust periods, each of which saw the Fed ease and then sharply tighten the money supply. These measures induced contractions in economic activity, but the Fed then failed to sustain its tighter policy long enough to yield a lasting decline in inflation. Again and again, short-term thinking led to uneven and irregular monetary decisions.

This dynamic began to change as the 1980s dawned. Some prominent analyses of the effects of discretionary fiscal stimulus — perhaps most notably that of economist Edward Gramlich in his 1979 study of the Carter stimulus packages — undermined the support for such policies among academic economists. On the practical side, the Reagan administration eschewed highly discretionary approaches in favor of greater reliance on fundamental (and permanent, rather than temporary) tax reforms.

This reliance on automatic stabilizers (rather than discretionary policies) in responding to the ups and downs of the business cycle continued through the 1990s, with very few — and very modest — exceptions. A very small stimulus was proposed by President Bush in 1992, but even this failed to pass in Congress. Another small stimulus was proposed by President Clinton in 1993, but it too failed to pass. By 1997, Northwestern University economist Martin Eichenbaum could write of the "widespread agreement that countercyclical discretionary fiscal policy is neither desirable nor politically feasible."

A similar shift occurred in monetary policy, beginning with the Federal Reserve's decision — starting in 1979 under the leadership of Paul Volcker — to focus its efforts on reining in inflation. This marked a dramatic change from most of the 1970s, when the Fed repeatedly switched emphasis from unemployment to inflation and back again. In his 1983 address before that year's AEA-AFA luncheon, Volcker noted that the Fed had "gone a long way toward changing the trends of the past decade and more." His successor, Alan Greenspan, maintained this commitment to price stability through the 1980s and '90s.

The Fed also showed a greater appreciation for the importance of predictability and transparency in its decisions. In the 1970s, decisions about interest rates were hidden within the Fed's announcements about its borrowed reserves. By the early 1990s, however, the Fed was announcing its interest-rate decisions immediately after making them, and was even publicly explaining its expectations and intentions for the future. The transcripts of meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee — the Federal Reserve body that makes decisions about interest rates and the money supply — throughout the 1990s include numerous references to policy rules.

The empirical evidence, too, plainly demonstrates that monetary policy corresponded far more closely to simple policy rules in the 1980s and '90s than it had in the previous two decades — as shown, for example, in a 1995 study by John Judd and Bharat Trehan of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

But this commitment to rules-based economic policy has waned in the last decade. Perhaps an early sign of the change was the Bush administration's decision to respond to the economic downturn it confronted in 2001 with a one-time "tax rebate" (in which $300 checks were sent to about two-thirds of American taxpayers) intended to stimulate demand. Though one could say this was a down payment on the more permanent 2001 tax cuts that followed, the administration's move led Milton Friedman to pronounce with regret that "Keynesianism has risen from the dead."

Clearer signs, however, could be found in monetary policy. Between 2003 and 2005, the Federal Reserve held interest rates far below the levels that would have been suggested by the monetary-policy rules that had guided its actions in the previous two decades. The deviation was large — on the order of magnitude seen in the unstable decade of the 1970s. The Fed's public statements during that time — which asserted that interest rates would be low for a "considerable period" and would rise at a "measured" pace — are evidence that this was an intentional departure from the policies of the 1980s and '90s.

Ostensibly, that departure was intended to help ward off a perceived risk of deflation, but the extremely low interest rates during these years contributed to the development of the housing bubble that played a central role in the economic crisis from which we are still recovering. The Bush administration then responded to the downturn that began in December 2007 with another round of exceptionally discretionary fiscal policy. First came a $152 billion stimulus package enacted in February 2008 (that again included checks to taxpayers). The following month began a series of on-again-off-again bailouts of the creditors of financial firms — on for the creditors of Bear Stearns, off for those of Lehman Brothers, on for those of AIG, and then off again while the Troubled Asset Relief Program was rolled out. During the ensuing panic in the fall of 2008, the government intervened to help the commercial-paper market and money-market mutual funds.

The next year, the Obama administration advanced an $862 billion fiscal stimulus (which included temporary rebates and credits, as well as grants to state and local governments) and the Cash for Clunkers program. The Fed then stepped in with more discretionary policy of its own, most notably its massive quantitative-easing policy in 2009 (which included the purchase of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities and $300 billion in long-term Treasury bonds). The Fed's second round of quantitative easing — which is popularly known as "QE2" and will continue into this year — is set to involve the purchase of another $600 billion in long-term Treasury bonds. All told, there can be little doubt that the rules-based economic policies of the 1980s and '90s are over.

DISCRETION, RULES, AND CONSEQUENCES

What effect did this policy cycle have on the economy? What happened to America's economic performance — measured through employment, inflation, stability, the nature of recessions and recoveries, and economic growth — as the pendulum swung back and forth between policies governed by rules and those based on discretion?

The three periods in question clearly coincided with dramatically different levels of economic performance. The first swing, toward discretionary policies, aligned with a period of frequent recessions, high unemployment, and high inflation from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. In fact, inflation, unemployment, and interest rates all reached into double digits in this period, and by the late 1970s there was a palpable sense in America that our economy was out of control, and perhaps headed for an enduring decline.

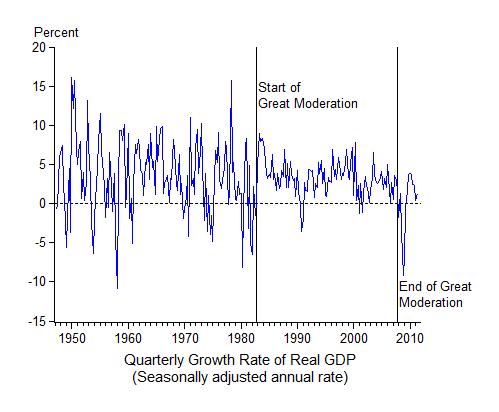

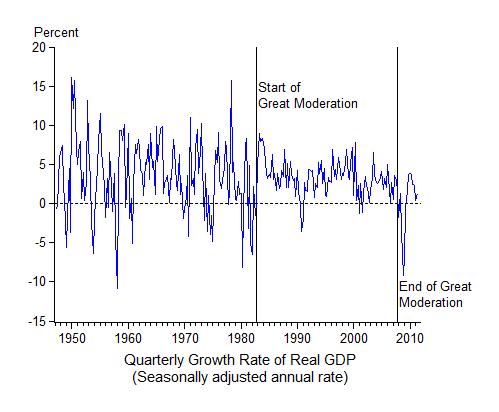

The second swing, toward more rules-based policies, coincided with a remarkably stable period, frequently called the Great Moderation, from the mid-1980s until the early to mid-2000s. Both the levels and the volatility of inflation and interest rates were markedly lower than they had been in the 1970s. The volatility of real gross domestic product, in fact, was reduced by half. Economic expansions in this period were longer and stronger, while recessions were shorter and shallower than they had been in the previous two decades.

Finally, the swing back toward discretion in recent years has coincided with the financial crisis and a recession much deeper than those of the Great Moderation period. The recovery, meanwhile, has been much slower than the one we saw after the recession of the early 1980s.

The economic history of the past 60 years thus suggests a connection between rules-based policy and good economic performance. But correlation — even an amazing six-decade-long correlation — does not prove causation, so we must investigate further.

First, we must consider the possibility that the correlation reflects a cause-and-effect relationship in the opposite direction — that is, that poor economic performance brought about more intervention, and good economic performance permitted less intervention, so that the swings were caused by changing economic performance rather than serving as the cause of it. The basic timeline laid out above, however, is completely inconsistent with such an explanation. The popularity of discretionary Keynesian fiscal policy in the 1960s could not have been a response to the deep recessions of the 1970s, after all. Similarly, the inflationary monetary policy that began in the late 1960s could not have been caused by the inflation of the 1970s. And it obviously strains credibility to argue that the Federal Reserve's move to reduce inflation and restore economic stability in the late '70s was caused by the low inflation and stable economy of the 1980s and '90s.

Perhaps one could more plausibly argue that the shift back to discretion in recent years was provoked by the severe financial panic of 2008. But much of that shift toward discretion began before the panic of the fall of 2008: Low interest rates were maintained from 2003 through 2005; the Bush administration's stimulus package was enacted in February 2008; the Fed's discretionary bailouts began in March 2008. Moreover, if the emergency of the panic were the reason for the move toward discretion, one would expect to see a return to rules-based policies now that the height of that panic is more than two years in the past. Instead, another large discretionary action — the Fed's so-called QE2 — has been undertaken, rationalized on the quintessentially discretionary grounds that the economic recovery is slowing and that even a monetary policy with interest rates near zero has not been easy enough to combat deflation.

The more straightforward conclusion — that rules-based policy was an important cause of the improved performance of the 1980s and '90s, and that discretionary policy has been harmful to the economy — aligns much better with the historical timeline. It is also amply supported by economic theory. Any dynamic model in which people are forward-looking and take time to adjust their behavior to circumstances implies that monetary and fiscal policy work best when formulated as rules. Government's adherence to known rules allows people to have a clearer sense of what is coming, and therefore to make more informed decisions and long-range plans.

The so-called "time consistency" argument developed by economists Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott — for which they won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2004 — further buttresses this view. In a 1977 article in the Journal of Political Economy, Kydland and Prescott argued that discretionary policies produce suboptimal results because they deny people the benefits of "policy commitments." Such commitments — which give the public the sense that the basic rules of the game are steady and reliable — are essential to the proper functioning of a market economy. Kydland and Prescott's argument suggests that a commitment to a reasonably sound rule — even if it is very far from a perfect rule — is preferable to discretionary policies, however well intentioned or managed. Moreover, almost by definition, highly discretionary policy limits the ability of market players to plan, and so tends to distort market behavior, driving it toward inefficient short-term responses and choices.

The so-called "Lucas Critique," named for economist Robert Lucas (who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1995), suggests that consistent rules are crucial for conducting and evaluating economic policy. First published in 1976, the Lucas Critique argues that, since people's expectations are heavily dependent on particular public policies, economic models that try to evaluate policy based entirely on extrapolating historical trends are bound to fail because they do not take policy changes into account. The same principle suggests that economic models will break down if policymakers do not follow relatively consistent rules — and therefore that rules have an essential role to play in guiding policymakers toward sound decisions, and in helping them assess the effects of their decisions. Over time, discretionary policy will inevitably make for bad policy.

Some observers have argued that the crisis of the past few years shows that economic models that assume rational forward-looking agents have failed — and that we should therefore discount this case for rules, which is based on such models. But the evidence of the past few years does not support such a view. It suggests instead that the models and theories were right, and that the policies pursued by policymakers in Washington were wrong — that the failure to adhere to rules-based policies contributed to the crisis. As Princeton economist Avinash Dixit put it recently, "economic theory came out of this rather better than policy practice did."

I have spent a good part of the past three years studying the implications of the past decade's turn to discretionary policies. My research shows that the low interest rates set by the Federal Reserve from 2003 to 2005 added fuel to the housing boom and led to risk-taking and eventually a sharp increase in delinquencies and foreclosures and in the toxic assets held by financial institutions. A more rules-based federal funds rate — particularly one that held to the general approach that characterized Fed decisions throughout the 1980s and '90s — would have prevented much of the boom and the bust that followed.

Other economists have found much the same. In a paper published last year by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, economist George Kahn observed that, were it not for the Fed's deviation from its general rule of the 1980s and '90s, the housing bubble would have been significantly less severe. "When the [policy rule] deviations are excluded from the forecasting equation," he wrote, "the bubble in housing prices looks more like a bump." Last year, Charles Bean and his colleagues at the Bank of England argued that the Fed's deviation from its earlier policy rule caused 26% of the increase in U.S. housing prices during the period of the boom — no small portion, given that housing prices have fallen by only about 30% from their peak. It seems clear that the Federal Reserve's discretionary measures played a significant role in setting up the severe recession from which we are still recovering.

On the fiscal-policy front, I have found that the tax rebates and one-time stimulus payments in 2008 and 2009 did little overall to jumpstart consumption and thereby jumpstart the economy, which their proponents insisted they would. Aggregate disposable personal income increased when the stimulus checks were sent out in the spring of 2008, but aggregate personal consumption did not increase. Similarly, the stimulus-induced temporary increase in disposable personal income in the spring of 2009 did not have a noticeable effect on aggregate consumption. Thus the evidence shows that, in the aggregate, neither stimulus package had any noticeable effect on consumption.

My Stanford colleague John Cogan and I have also found that the parts of the 2009 stimulus aimed at boosting government purchases were similarly ineffective. Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis show that government infrastructure spending at the federal level increased by only 0.04% of GDP due to the stimulus. And the grants sent to state and local governments also did not actually result in an increase in government purchases of goods and services (perhaps in part because many states and localities merely used them to plug holes in their budgets).

To be sure, the Fed's interventions in the commercial-paper market and money-market funds during the panic in the fall of 2008 — measures intended to provide liquidity to those markets — were helpful in rebuilding confidence. So not every discretionary intervention in recent years has been harmful, but those more effective interventions would not have been necessary had the earlier interventions been avoided.

On the whole, the past few years leave little doubt about the dangers of discretionary economic policy. And the evidence left in the wake of the policy cycles of the past six decades strongly suggests that rules-based policymaking is a far superior approach.

POLICY RULES AND ECONOMIC FREEDOM

The case for rules over discretion is not only an economic case. As Friedrich Hayek put it in The Road to Serfdom in 1944,

Nothing distinguishes more clearly conditions in a free country from those in a country under arbitrary government than the observance in the former of the great principles known as the Rule of Law. Stripped of all technicalities, this means that government in all its actions is bound by rules fixed and announced beforehand — rules which make it possible to foresee with fair certainty how the authority will use its coercive powers in given circumstances and to plan one's individual affairs on the basis of this knowledge....the discretion left to the executive organs wielding coercive power should be reduced as much as possible.

It is no coincidence that the same approach that best serves the interests of freedom and the rule of law also makes for good economics in practice. In both cases, setting out a rule and sticking to it helps policymakers resist interest-group pressure and avoid overreacting to short-term blips. It allows citizens to exercise their freedom and their judgment, and enables both the people and their leaders to keep their eyes on long-term needs and goals.

As former Treasury secretary George Shultz put it to yet another joint luncheon of the American Economic Association and the American Finance Association (this one in 1973), "economists have a particular responsibility to relate policy decisions to the maintenance of freedom, so that, when that combination of special-interest groups, bureaucratic pressures, and congressional appetites calls for still one more increment of government intervention, we can calculate the cost in these terms...[and so] may have an impact on policy that extends beyond the most current crisis and reflects the best traditions of this discipline."

The best traditions of economics today demand an engagement with the facts of the past 60 years, informed by the theories built up in that time. Those facts and those theories argue against the recent reversion to Keynesian discretionary interventionism, and for a revival of the kinds of rules-based fiscal and monetary policies that have yielded unmatched stability and economic growth.

[u]

[u]

Yuri Yukuv- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 1974

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 78

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

She is so stupid

guest7- Fan Favorite

- Club Supported :

Posts : 8276

Join date : 2011-06-05

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Yuri Yukuv wrote:You have a great reply, however I disagree with you on something and I think you are slightly misinformed in others. I will come back to answer by the weekend.

For now however I will adress part of your reply with an article written by Taylor himself

This is a great read for anyone

That was a great read Yuri. It seems like there are any basic principles that make a lot of sense masquerading as a number of different theories. But yeah, this makes a lot sense.

Do the rules exclusively refer to automatic stabilizers or does it include other concepts too?

And how to you implement this automatic stabilizer in the economy? Through taxes?

kiranr- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 3496

Join date : 2011-06-06

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Paul is far too radical for a largely central leaning nation like the US. Many of us come right down the middle on most issues, occasionally leaning right or left here and there, but Paul is just too far on one end of the spectrum as that's why he'll never be president. Just about all of those candidates are too far right, except maybe Romney and in some ways, Gingrich.

Conservatives incorrectly accused Obama was being too far left, but as his campaign went on and his presidency began, he steadily got closer and closer to the center to his present position: center-left essentially.

Conservatives incorrectly accused Obama was being too far left, but as his campaign went on and his presidency began, he steadily got closer and closer to the center to his present position: center-left essentially.

McLewis- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 13350

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 35

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

is it me for Paul the only ones out of all the candidates to doesn't want more wars.... all of them yesterday wanted to go to war with Iran and even Syria....

and i don't get that how they blame Obama for the debt and overspending on the wars but while wanting to go to more wars and improve their army...wouldn't that further increase the debt....

and i like how paul is the only one that asks why Al-Qaeda only attacks US and UK? why not Sweden or Norway or others who have some ideology as them..All the others candidates say that US's ideology is the reason they do....but then why don't they target the others...they seriously need to ask that question

and i don't get that how they blame Obama for the debt and overspending on the wars but while wanting to go to more wars and improve their army...wouldn't that further increase the debt....

and i like how paul is the only one that asks why Al-Qaeda only attacks US and UK? why not Sweden or Norway or others who have some ideology as them..All the others candidates say that US's ideology is the reason they do....but then why don't they target the others...they seriously need to ask that question

TalkingReckless- First Team

- Club Supported :

Posts : 4200

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 32

Re: Time for a libertarian president

Re: Time for a libertarian president

That's certainly a strength about Ron Paul. He's never afraid to ask the questions that will make us think. He's not pandering constantly to his base like the other 6 candidates are doing and if his overall economic views weren't so damn radical...he'd make a good opponent for Obama.

McLewis- Admin

- Club Supported :

Posts : 13350

Join date : 2011-06-05

Age : 35

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Similar topics

Similar topics» Juventus President Andrea Agnelli suggested major Leagues all start at the same time to “harmonise European football.”

» A libertarian view of the housing bubble

» Countries + Cities + Time zones. + Ages, save me the time of looking at I-no's thread >>

» Idea on how to stop Fergie time and time wasting in general

» All-Time Real Madrid vs All-Time FC Barcelona

» A libertarian view of the housing bubble

» Countries + Cities + Time zones. + Ages, save me the time of looking at I-no's thread >>

» Idea on how to stop Fergie time and time wasting in general

» All-Time Real Madrid vs All-Time FC Barcelona

Page 1 of 2

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

» Serie A 2023/24

» Bundesliga 2023/24

» General Games Discussion

» Manga and Anime

» Introduce yourself to the community - Topic 2

» Real Refdrid, Real Uefadirt, different names, same schemes.

» La Liga 2023/24

» Florentino Perez - man of mystery!

» The Official Dwayne Wade <<<<<< you thread

» Modric considering one more year!

» Political Correctness, LGBTQ, #meToo and other related topics

» Manchester United Part V / ETH Sack Watch